The Chinagraph Pencil Management Organisation: a cautionary tale

“Well Sir, today’s training serial was very pleasing in most respects but I’m afraid there was one critical shortcoming that makes the overall assessment Below Standard”

“Sorry Staff, what? But we aced it! Everything you threw at us we dealt with and well inside the Fleet standard times for all evolutions.”

“Ah, yes Sir but I took the opportunity during a lull in the action to check on your Chinagraph Pencil Management Organisation and it seems to be non-existent; so, it’s a BS I’m afraid.”

“Our chinagraph what?”

“Yes Sir, the CPMO is a new requirement that is set out in a draft RNTM[1]”

“A draft RNTM? ie, one that has not been issued yet?”

“Yes, it’s in draft but we’ve had it agreed by our higher-ups that it’s already a mandatory requirement.”

“Aside from the problem of not being clairvoyant, what do we need a ‘CPMO’ for anyway – each Incident Board Operator[2] is responsible for having the necessary equipment for their role?”

“Ah, that’s where the problem is. How do you assure that each IBO has the right equipment or, if the IBO is a casualty in the incident, how would you ensure that the Incident Board could be correctly marked up? If you can’t do that you won’t be able to exercise effective Command and Control over the emergency and that could lead to losing control of the incident potentially meaning multiple loss of life and mission failure. It doesn’t bear thinking about Sir, but it’s a credible risk and the CPMO is just basic risk management really.

That’s why you’ll need to have a CPMO up and running in time for tomorrow morning’s serial or it’ll be another fail I’m afraid, and we’ll have to declare you unsafe to be at sea. It doesn’t take much; just a CPMO Log with the correctly formatted paper sheets where everybody can sign for their chinagraph pencils and annotate the location for stowage of spares. This is the responsibility of a CPMO Manager, assisted by a Deputy CPMO Manager; and both of these should be nominated in a Commanding Officer’s Temporary Memorandum to be stored in the first section of the CPMO Log. Oh, and a training plan to ensure that everybody is au fait with the procedure managed by the CPMO Training Officer. Obviously, you will need to check the Log monthly and the Warrant Officer should check it weekly.

Have a nice evening Sir.”

The vignette above is simultaneously fictitious and yet entirely familiar, in its essence if not the specifics, to generations of Naval Officers that have led their departments and ships through operational training and other assurance activities. I use it to illustrate the point I intend to make in this blog article but I should stress that I am talking about bureaucracies in general, not specifically those of the Navy or Defence.

This is how bureaucracy grows; it is fractal[3]. That is to say, self-similar at differing scales. As you “zoom in” on a process you will find, in increasing resolution, layers of process and risk that need to be managed, quantified and assured. By doing this you get an increasing “quality” of process where more variables are found to be controlled and increased layers of assurance and governance are required. And so the bureaucracy grows. This is not an irrational proposition, especially for the functional process owners whose responsibility to the organisation is not for its outputs but for having the highest quality functional processes possible. This is what the system demands of them and, as professionals, what they take pride in delivering. Once you have improved your process, by reviewing it and addressing any identified shortcomings, you will have a higher quality process. Owing to the fractal nature of bureaucracy, this leads to a geometric increase in process and management overhead in an organisation over time and iterations of change. And it is a one-way valve; a diode. It goes against the grain to say to someone “reduce the quality of your process by zooming out and dealing only with those issues which are visible at a macro level.”

Especially in hazardous industries, like Defence, who spend a great deal of their time preparing for and managing very low probability but high impact events (so called “tail risks[4]”) there is (and must be) an obsession with ensuring that details are attended to, and excellence is a habit in all that you do. Only by taking such an approach can you maximise your readiness for extreme events and minimise the number of ways your response to extreme events could be flawed. Systemic risk does not scale linearly and, again, is fractal in nature (the bureaucracy, remember, is an organisational response to the identification of risk at different scales). This means that to minimise the probability of adverse outcomes from extreme events from happening one must take action that is disproportionate to the individual, local risk.

Taleb[5] explains this in the context of measures necessary to control pandemic spread:

So, the system incentivises the bureaucrat, for all of the right reasons, to ensure that the processes that they are responsible for are not the cause of systemic failure, even in extreme events. It is therefore rational for them to ensure that the functional processes for which they are responsible are watertight. Ally to this the human inclination of maximising one’s own professional jurisdiction for reasons of job security and prestige in the organisation and you have a dynamic that moves in one direction. To explain how this manifests, I humbly posit the eponymous “Prest’s Law of Bureaucratic Reform”:

Whenever an administrative process is reformed by the process owner, usually with the intent of making it less onerous, the revised process invariably ends up being more onerous for the user than the previous one.

When we zoom-out to the organisational level though, this makes no sense. What I have described is the risk-averse drift toward bureaucratic paralysis. The aggregation of individually rational actions leads to, overall, a sub-optimal outcome. Thus, strategic leaders (and process users) will rail against the macro effects of the bureaucracy inherent in the system which stifles the pace of progress and erodes efficiency. In other words, they can see the macro cost to the organisation of bureaucratic inertia; costs which are hidden from the process owners at the local level whose primary focus, quite naturally, is the goodness of their process, not the pace and efficiency of output delivery.

The response of leaders is often to exhort their organisations to “take risk” against process. But it is not normally clear who is empowered to judge the risk appetite. Is it the process owner who is, in effect, being invited to short-cut their carefully crafted functional mechanism – why would they do this? Or is it the process user? If a user is not required to conform to a policy or process, how does the organisation assure itself that the unacceptable risk is not being taken, that its resources are being used wisely and its reputation is being protected?

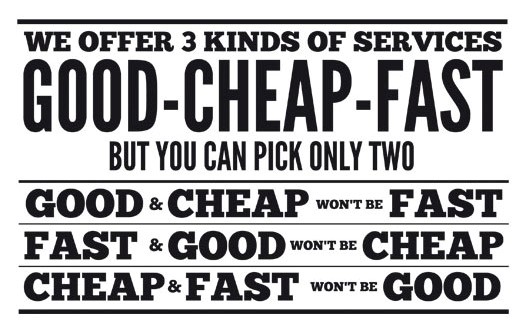

To unlock this paradox, the organisation must link the cost of process to the design of it. I would propose that a mechanism must be found of quantifying the total cost of a process, at the local level, and that this must be objectively (or at least independently) assessed so as to avoid cognitive (optimism) bias by the process owner. How much does it cost for a process to be satisfied to deliver an output? The manager, sufficiently senior to be accountable for both the output and the process, must then set the maximum value of the process that they are prepared to tolerate informed by their risk appetite. The process owner, in consultation with the user, can then be responsible for producing the best possible process for the cost that the manager is prepared to pay for the benefits that process gives (which may include risk avoidance or mitigation). The rational problem for the process owner is not, then, to create the best possible process but, rather, the best possible process to meet the process’s purpose that conforms to the “budget” set by the manager. The risk appetite is thus owned by neither the process owner, nor the user, but by the manager whom is served by both.

If the Directing Staff in our opening vignette was set the task of creating a CPMO that takes no more than 1 person-hour per year per ship, they may conclude that it’s not worth the effort and that, after all, just ensuring that everyone has access to a spare set of chinagraph pencils might be the organisation’s preferred answer after all!

[1] Royal Navy Temporary Memorandum: official notices that detail administrative arrangements and policies that are either time limited or have yet to be incorporated into Books of Reference (BRs).

[2] Incident Board Operators (IBOs) use chinagraph pencils, or their more modern equivalent –Overhead Projector pens (ask you parents kinds) to mark up Damage Control Incident Boards around the ship in the event of emergency so that the Command and Control of Firefighting and Damage Control can be exercised using a common understanding of the situation and events.

[3] Gluck J, Chaos, Random House (London: 1997), p103

[4] See the writings of Nassim Nicholas Taleb

[5] https://twitter.com/nntaleb/status/1239243622916259841?s=20 (posted 15 Mar 2020, accessed 21 Oct 2020)

By the very fact that you are here today, having had the courage to volunteer to join the Royal Navy, to have gotten on the train or aeroplane to come here 10 weeks ago and have subjected yourself to the initial training regime in the most successful fighting force the world has ever known, undefeated in over 400 years, sets you apart from your peers and from the rest of society. But with that accolade comes quite a responsibility. You now, as all of us in the Naval Service do, carry the responsibility to continue that tradition; that sense of duty and service. I will offer a few words of advice about how to succeed in that endeavour. These will not be a surprise since they are the very things that the training staff, have been instilling in you over the last 10 weeks.

By the very fact that you are here today, having had the courage to volunteer to join the Royal Navy, to have gotten on the train or aeroplane to come here 10 weeks ago and have subjected yourself to the initial training regime in the most successful fighting force the world has ever known, undefeated in over 400 years, sets you apart from your peers and from the rest of society. But with that accolade comes quite a responsibility. You now, as all of us in the Naval Service do, carry the responsibility to continue that tradition; that sense of duty and service. I will offer a few words of advice about how to succeed in that endeavour. These will not be a surprise since they are the very things that the training staff, have been instilling in you over the last 10 weeks.